India once had many large forests. Urban demand for wood and minerals have demolished most of our forests. The Government till now was brazenly indifferent to the fact that forest dwellers were being dispossesed The latter were never ever consulted. Today, less than 20% of it is forested. 12% of this area is in about 7% of the land that is known as India's North East. Yet, denudation continues as people are still to be given title deeds to the forest lands that have been their homes for centuries. Since 2007 India has a forest dweller friendly forest act but it has not yet been implemented forcefully. On many forest clearances in Arunachal and Manipur opium is being grown.

(Opium poppy flowers)

1. In early 2007 India enacted the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006. { http://tribal.nic.in/ & http://tribal.nic.in/writereaddata/mainlinkfile/File1033.pdf}. An Amendment in 2012 {http://tribal.nic.in/writereaddata/mainlinkFile/File1434.pdf} prescribed a monitoring system.

'The tall branchless trees give an idea of the dense forest that once existed here in Saraipung, Upper Assam, India. They had no branches as they were packed closely together, and only when they reached sunlight would they have branches. Brazen felling of trees have opened the forests of the North East for more exploitation. The rights of the indigenous people who dwelt in places like these were ignored.'

2. This new act is similar to FAO’s guidelines {http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/cfs/Docs1112/VG/VG_Final_EN_May_2012.pdf}. The Ammendment of 2012 and Chapter 3 of FAO’s paper headed “Civil Society perspective on monitoring in the context of the Voluntary Guidelines” are identical.

3. The new Act recognizes the forest dwellers rights to live, hunt, fish and till within forests, permits access to forest resources and protects them from eviction. The most important feature is that forest dwellers’ lands can only be bequeathed and not sold, and have to be owned jointly by husband and wife. And no one can hold more than 4 hectares of land.

'At the base of a thick forest this plywood factory was started in the 80s in Khonsa, E. Arunachal Pradesh. An opium growing area. The Forest Rights Act of 2007 has given hope that such kinds of exploitation will end. '

4. It guarantees title deeds to land tilled by forest dwellers. The title deeds have to be recommended by the entire village with one third of those present being women. If land rights are given they can benefit from development schemes and be protected from exploitation. Assured of control over their land, and not having to shift fields will mean an economic boost. Some could leave opium cultivation.

5. Expectedly, two opium growing states in the North East- Arunachal and Manipur- have not implemented this Act. For, if they did so, no land would then be sold and all lands that have been fraudulently acquired could revert back to their original owners, which is repugnant for a powerful few. In Manipur opium gum is extracted, dried and stored as gum. In Arunachal it is extracted and then spread on jute or nettle cloth and sold in small pieces.

'Cloth opium'

6. Arunachal is an ethnic people’s state, and it is governed by elected representatives, most of whom were once forest dwellers themselves. A few people have hundreds of hectares each, and in one case (Manthi village in Kamphai Reserve Forest) a thousand hectares allegedly belong to one person! Had the new forest act been enforced this could never have happened.

7. I shall focus on Manipur and Arunachal. In the former Alternative Development has not worked and in the latter AD will not work! Chandel, Senapati, Imphal, Thoubal and Ukhrul in Manipur, and Yingkiong, Passighat, Changlang, Tirap, Lohit and Anjaw in Arunachal grow opium and under the present circumstances will continue to grow it.

8. In Manipur’s valley and mountains opium cultivation started about six years ago- only for profit. Now they are demanding legalisation. Only in Chakpikarong Sub Division, bordering Chin State of Burma, had opium cultivation on swidden land been traditional. The average size of the fields is about 20 X 30 mtrs. The yield is 20 kgs a hectare. In Manipur few consume opium, which is sold at about $500/- a kg. to adjacent Burma’s Sagaing and Chin states. It is grown in the irrigated valley and in the denuded hills. The hills have also harboured vast swathes of cannabis cultivation despite development. The cultivating areas have roads, electricity, phones, schools, colleges and hospitals. This is an insurgent hit state and the rebels are profiting from this activity too. Several recent large seizures of opium, and a seizure seven months ago of a mobile heroin laboratory with 7 kgs of opium, 1 kg of heroin and chemicals have shaken the Government.

9. Manipur’s hill areas are dominated by Tangkhul Nagas- a highly educated tribe that has been developed for generations. Many of its people are influential bureaucrats, politicians and highly paid professionals. Yet some support rebels. Their mountains have been devastated of trees because of collusion with timber lobbies. Many of the cleared areas have been used for cannabis, and some are under opium cultivation. However, if title deeds are given slash and burn lands will convert to terraced and irrigated fields and farming would become more profitable. Opium could then be history as the law provides for confiscation of opium fields. Commercial cultivation, such as this, can be discouraged only by enforcement.

10. Arunachal has about 2.5% of India’s area but, despite indiscriminate logging, it still has 14% of its forests. In Lohit and Anjaw districts that border the hills of Burma’s Kachin State, opium has been grown for centuries on slash and burn land- known as jhum. The community decides which part of the forest is to be cleared and cultivated. Three decades ago the jhum cycle was about 30 years, but now it is 2 years. The reason is that forests are being cut rapidly by timber contractors and big businesses – from outside Arunachal- that require those giant trees for manufacturing plywood and furniture. This is done with the collusion of local leaders. In swidden fields felled trees were burnt for fertilizer and now that they cannot have.

11. Officialdom notices opium cultivation intermittently. From 1988 eradication started. There was no development in these two districts then. They were isolated and very poor. No health schemes, extreme destitution, only one road, no electricity, no jobs, shabby schools, no health care and no markets for their agricultural products. Individual opium plots were small, around 5 X 10 mtrs, and cultivated mostly by women. The yield hovered around a miserable 2 kgs per hectare. Opium cultivation and use was opposed by the youth in the 90s. A combined and sustained onslaught of eradication and urgent development followed. There are many roads, buses, many taxis, hydel dams, health centers, small businesses, jobs, phones, internet, banks, ATMs and contracts for locals. Even jewelers and traders from the plains have opened shops there. Life of almost half the population improved. A gigantic change for the Mishmi tribe, many of whom had led an impoverished existence a decade earlier. By 2000 opium cultivation had decreased by more than half and had retreated to clearings deep inside forests and over the ridges.

12. Then something happened. I cannot understand why. Maybe it were the reluctance to give scholarships, medical relief and agricultural grants and loans that were given smoothly, simply and quiuckly till the end of the 90s.

13. Perhaps it was political patronage by the elected representatives or maybe it was the demand from adjacent Kachin areas in NW Burma or both or more. From 2002 not only did opium cultivation balloon but the youth were addicted, including some women- something that was unheard of earlier. Opium fields are everywhere – in large fields by road sides, in kitchen gardens, and even within Tezu, the only town in these two districts.

These fields replaced dark, dense and immense forests. The Mishmi’s steady customers were the Khamptis and Singphos living in lower Lohit district. The latter paid for their opium by cutting down forests. After the forests finished they started cultivating opium themselves, and all three tribes are now looking for more customers elsewhere. And women mainly manage the cultivation and sale of opium.

'Selling cloth opium'

14. The average sized plots have increased to 10 X 20 mtrs and the yield is above 20 kgs per hectare. 11.7 gms (a tola) of cloth opium in season (March - April) is sold at farm gate for between $5-6. A kilo (83.7 tolas) for about $ 420/-. After keeping opium for their own use an average family makes about $1000-1500/- annually by selling opium. And tree cutting goes on to make way for more opium cultivation.

15. There are two kinds of cultivators. Rich and poor. The rich occupy land or

slash vast dense public forests to cultivate opium. They also get to own orange orchards, cardamom plantations and tea estates. The poor own small fields, which produce opium for their own needs and a little for barter and sale. They also cultivate on lands that once had forests. Under the new Forest Act only 4 hectares of land at most can belong to one family. A few have a thousand hectares or so. That is why Arunachal is not implementing the Forest Act of 2007.

'A large opium field in a jhummed or swiddened clearing in Raliang village, Hayuliyang Circle, Ajnaw Distirct, Arunachal.'

16. The rich threaten violent action if there is eradication and the poor fall in line as their willing soldiers because of their abnormally high consumption of opium. This violence has kept selective enforcement at bay! However, if they are given title deeds to their lands it will eventually end swiddens and increase their income, provided they can chuck smoking opium. However I must add that those living far from the roads are still poor. For them opium is still the only medicine available, and they also barter it for essentials like grain, cloth and kerosene oil. Wide spread development has profited only a few.

'

A poor man's low yielding opium field in Kondong village, Anjaw District.. The opium he uses to exchange for kerosene oil or better quality rice'

Anjaw Distirct:

A poor opium cultivating man's wind swept hut in Kondong village. This is how some live- in 2012.

'

A rich opium farmer's house in Raliang village, Anjaw. Note the solar panel to the right.' Raliang, Anjaw Distt.

17. Eradication cannot make them leave opium, and most do not wish to do so till they are consulted about opium use and cultivation. The only time that their voices are heard is after every five years during elections. Then they are plied with alcohol and opium and assured that their traditions will not be touched- meaning that opium cultivation will continue. Opium as a commercial crop is crucial to the leaders’affluence and influence. It is because of this that they encourage the tradition of slash and burn for it allows them to buy more cleared land. That is also why not one title deed has been given, while in Tripura, a North Eastern State, out of 182,617 claims received 120,473 deeds have been distributed till September, 2012, and the few small pockets of opium cultivation have gone.

18. High opium usage is the reason why development and restitution of land rights alone will not succeed here. As long as people continue to use opium it will always be cultivated. Many treatment centres have to be set up. At the moment there is only a squalid one at Lathao. Tezu hospital has had one for years, but it is not yet open. If the Government were to supply the users with opium, as was done from 1972 in other parts of India, they would stop growing opium for themselves.

19. It is also urgent and necessary now to

discuss the problem with the people. In 2000 a sample survey of Lohit and Anjaw was done by the Central Bureau of Narcotics, where I was working. The UNDOC also participated. Of the 82 villages surveyed 55 grew opium but their yield was rarely above 200 gms per field. Now it is 3 kgs. Opium use amongst the young has increased by more than 50%. In early 2010 some of us based in Delhi and helped by 27 youth from the Mishmi, Singpho and Khampti tribes had, at the request of Arunachal Government, surveyed opium cultivation and its use in here (Report at http://www.narcoinsa.com/pdf/arunachal-opium-survey-report.pdf). Consulting the people was stressed by us in that report and at a meeting with the Government 10 months ago. The Government is still silent. The Central Government can only think of enforcement, which will not work. The State Government does not want to think. There are no NGOs working in this field. The future is bleak.

20. Development-led approach in India has not worked. Maybe it has not worked anywhere in the world either.

Unless the long term opium users, who are myriad, are given their requirement of opium under medical supervision all such crazy castles built on the quick sand of Alternative Development will sink.

21. I shall end with some figures from the 2010 Report on Opium Cultivation prepred by the Institute for Narcotics Studies and Analysis, New Delhi (http://narcoinsa.con). These indicate a proliferating problem that no amount of development will be able to control:

Some stats from

ANJAW & LOHIT districts:

Population 22,000 (approx.) & 142,000 (approx.) respectively-

Area 6190 sq. kms. & 11402 sq. kms.-

Families cultivating opium 90% & 63% respectively-

Opium main income source for 186 out of 226 villages & 95 out of 232 villages respectively-

Land under opium cultivation 3460 hectares & 12981 hectares-

87.8% of all surveyed in opium cultivating

villages of ANJAW & 96% of all in opium cultivating villages in LOHIT say cultivating opium is more profitable than any other crops-

Number of men users 1703 & 7825 respectively-

Number of women users 210 & 1075 respectively-

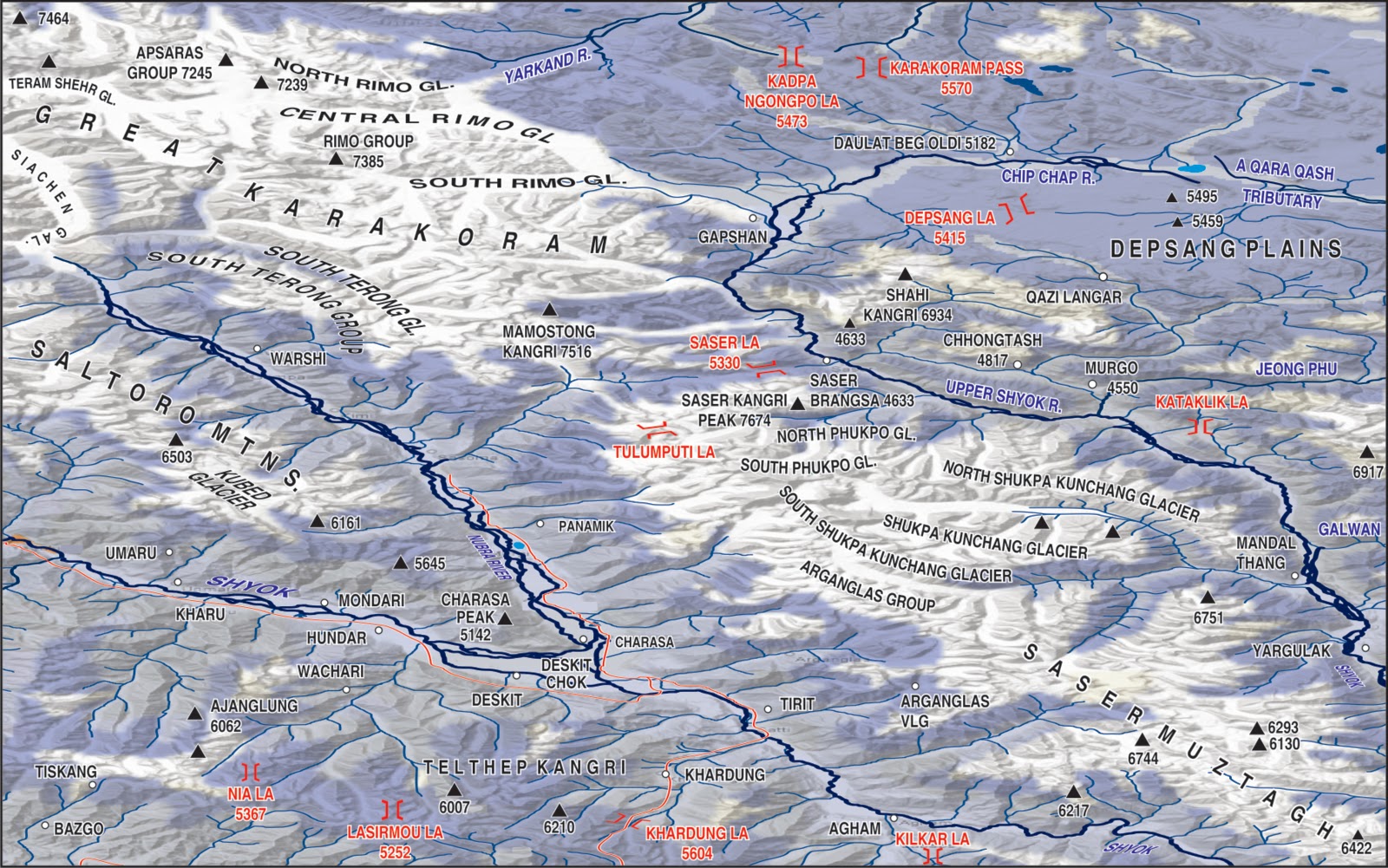

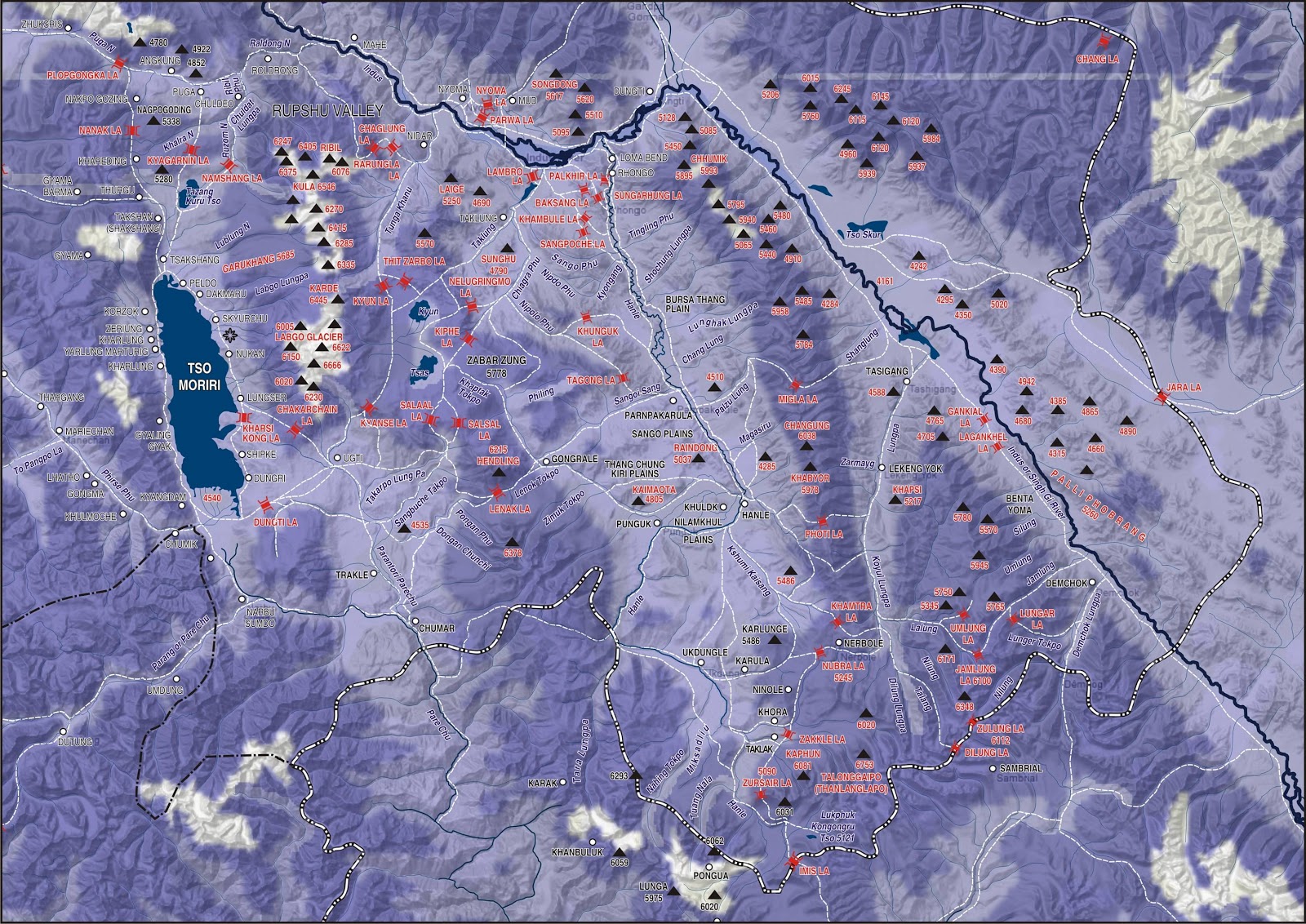

Map of Arunachal Pradesh showing the six opium growing districts>

Paper read at a TNI Dialogue, Bangkok, 17th December, 2012